Urban Planning Toolkit in Canada

Presenters at Nordic Urban Lab 2018: Sarah Douglas-Murray & Ali Sabourin

Creative Cities Network of Canada (CCNC) is Canada’s national network to facilitate innovation and creativity in municipal structures. They support cultural development by sharing knowledge between municipalities and enhance social, economic and environmental sustainability.

Both Sarah Douglas-Murray and Ali Sabourin are board members of CCNC. Sarah Douglas-Murray is the senior manager of Cultural Services for the town of Oakville.

The Cultural Services division is working with the implementation of the cultural plan 2016 – 2021 and has so far been very successful in terms of growing the capacity of cultural groups within the community.

Ali Sabourin is the senior project manager for the project ‘Love Your City’ located in Hamilton. She is working with developing cultural planning, mapping cultural resources and engaging citizens and stakeholders in a cultural policy of the city of Hamilton.

Douglas-Murray points out some of the challenges within CCNC;

Every province has its own provincial ministry of culture, and these does not always align. For example; Oakville is a part of the Halton county, which includes five other cities, which has its own plan, which need to fit in the provincial frameworks, and also at a national scale, which can add a lot of complexity. Mandate for culture is often split, and municipalities has a big range in size. Resources & organizational structures are extremely diverse and the expertise and training in cultural planning are limited.

The Importance of a Cultural Plan

CCNC has developed three different kinds of toolkits; Cultural Mapping Toolkit, Public Art Toolkit and Cultural Planning Toolkit, of which the latter one is the one described in the presentation at Nordic Urban Lab. The Toolkits can be found and are free to download on CCNC’s webpage.

The toolkits are targeting community leaders and organizations, local government staff, elected council members and partner organizations.

In the toolkit of cultural planning, a set of arguments are presented of why cities need a cultural plan. A cultural plan can help with combatting the social exclusion of a community and to tackle the “geography of nowhere” by supporting local community initiatives to provide a sense of pride of their city. By supporting, encouraging and promoting local involvement, cooperation and ownership, a cultural plan can identify the community needs.

Logically, different cities needs different cultural plans. The main purpose and priorities needs to guide you in which direction your cultural plan should go.

In order to choose the right one for your place, it might help to consider the following questions:

Do you need to develop a comprehensive detailed cultural plan which broadly defines the understanding of culture? Or do you need a framework plan which is aimed more towards a goal in the long run? Or maybe you need a specific short term plan that has mainly a single focus, such as the art sector, heritage or tourism? The toolkit aims to help with these issues.

The Cultural Planning Toolkit

Preparation is the first step in the cultural planning toolkit and cannot be underestimated.

The toolkit encourages you to think about your community’s definition of culture.

Cultural planning is a dynamic and emergent practice, which challenges presumptions and long accepted vocabulary. Douglas-Murray emphasizes that words can mean different things for different people and language is something that should be highly considered in the cultural plan. That is one of several aspects of why careful preparations are needed.

Examples on which preparations that could be necessary; Read, ask questions and asses what already has been done. Build partnerships, and for this the toolkit provides a checklist. Create an understanding of decision makers in order to make the implementation go smoothly. Do research on funding opportunities.

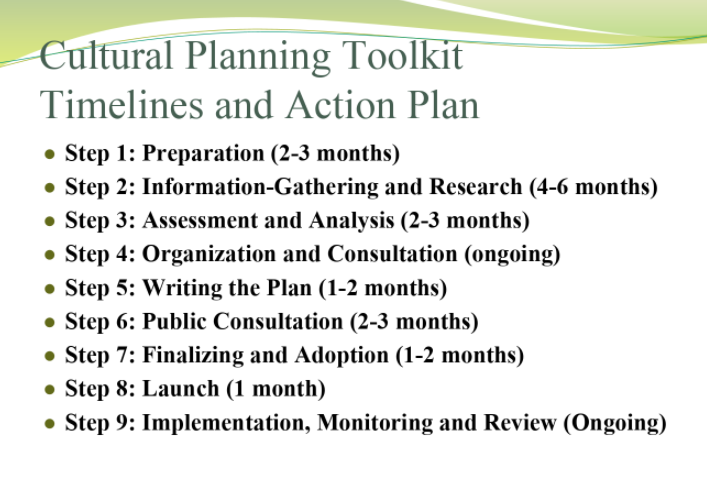

The toolkit is providing a step-by-step timeline and action plan for a cultural plan.

Make sure that everyone involved in structuring the plan understands that this is not something that can be rushed in order for it to be feasible. The toolkit encourages you to always remember to keep in touch with the people you have been consulting with. Test your results and identify priorities.

“Talk to your community, everything can’t be done at once, try instead to see what can be done and when. You don’t want to send out expectations that you are not going to be able to deliver on.”

When starting to write the plan, you need to make sure you use your data in order to make YOUR case for culture. Outline your key findings and do more consultations. When launching tell people what you are going to be doing and then move on to implementing, monitoring and review.

Douglas-Murray ends her presentation of the toolkit by giving some tips on other resources that could be used in cultural planning. The university of British Columbia has an online cultural planning certificate program, which takes about two years, but the courses can be taken individually. There is one specific course on cultural planning which takes ten to twelve weeks. If you have the time and resources, that is another tool which Douglas-Murray is recommending.

Oakville, Ontario, Canada

Oakville is located between Toronto and Niagara falls and has a population of 192 000 inhabitants. It is a suburban community and people commute to close bigger cities.

They had their first cultural plan in 2009, and the next one started in 2016 and will be ongoing until 2021. It focuses on what Oakville, as a municipality, can leverage and lead. They use the toolkit for their plan all the way through. After their first plan, Cultural Services wanted to update the plan, simply because it was so successful.

For example; thanks to the first plan, they were now running events and were able to set up a new Events Department to assist and coordinate events. They also manage to establish many new partnerships and set up new art programs, both public and corporate. Since Oakville’s first cultural plan, Cultural Services learned to see, through their community, emerging trends and the need to broaden their definition of culture.

“Culture is more than the typical western traditional definition of culture such as paintings, music and theatre; our community wanted more”.

Some key findings were the towns cultural anchors. And as cultural anchors Douglas-Murray points out some of the towns buildings, such as the theatre and museums, but also the facilitators and providers of culture. Oakville had over 50 non-profit organisations and they saw the need to find a better way to support them. The value of diverse culture was recognised.

Hamiltons Cultural Resources

Hamilton is a city with a long and proud blue collar history, mainly because of the steel work, which used to rule the economy. Hamilton has been nicknamed both “Lunch bucket city” and “Steeltown” because of this. But it has more to offer than steel. It has many green wonders, the bay and over 100 waterfalls. It has more than 500 000 inhabitants and is the 10th largest city in Canada.

Ali Sabourin further describes Hamilton; “We are a shedding Steel Town, although it remains as an important part of our narrative”. Sabourin also says that sometimes the artist has the most interesting depictions, and shows an image that says; “art is the new steel”.

Hamilton is no longer ruled by steel, the top employer is now Hamilton Health Science.

As Oakville, Hamilton is working with a cultural plan, and the project ‘Love Your City’ is a major campaign in branding the city and is a part of the cultural plan. The project built new partnerships, for example with the library, and aimed to increase the understanding of a cultural policy. In 2004 the City Council gave a green light to develop a cultural plan. It took four years to get the funding and resources needed from The City and in 2008 they were ready to start the first phase. Phase one started with a cultural mapping, in order to define the city’s cultural resources. This was completed in 2010 and the cultural policy was adopted in 2012 and then finally the cultural plan was approved in 2013. Even though it took nine years to go from an idea to an actual plan, there were many supporters and projects along the way, and it was presented in the news as a game changer for Hamilton.

See Douglas-Murray and Sabourins powerpoint from Nordic Urban Lab HERE

Sabourin further states that it is important with engagement and endorsement for any cultural plan and that it is the key to success. In phase two and three, they used methods which included the voices of 2300 citizens in order to base the cultural plan on the people of Hamilton. They had for example a round-table-meeting with cultural leaders, public workshops, a storytelling program to forward diversity and uncommon voices, an online survey and a citizen reference panel. All the above are the basis for the cultural plan. In the online survey 92% of the 1100 hamiltonians answered, that they believe culture adds to quality of life.

The members of the citizen reference panel was chosen randomly. 5000 letter were sent out to the citizens and of them 200 said yes to be a member of the panel and 30 people were chosen. There were no demands on knowledge about culture.

The cultural policy of Hamilton is built on the fourth pillar language, which includes culture as the fourth pillar, next to the three established pillars of society; social, economic and environmental.

Every year the City Council receives an update on the cultural plan’s progress and today Hamilton is a city with strengthened partnerships and increased community capacity. They have a cultural statistics strategy, a city enrichment fund with arts program and programs for community, culture and heritage. They support corporate initiatives, for example they are now mapping the surrounding agriculture and the aim for the future is to keep positioning culture as central to city building.

Documented by: Eira Bonell, Malmö University, 22.3.2018